5 Myths of Tarring and Feathering

Philip Dawe’s “The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering” (31 October 1774). Source: Library of Congress

1. Myth:

Tarring and feathering could be fatal.Busted:

The notion that hot tar caused severe, sometimes fatal burns is based on the assumption that “tar” meant the asphalt we use on roads, which is typically stored in liquid state at about 300°F (150°C). But in the eighteenth century “tar” meant pine tar, used for several purposes in building and maintaining ships. As any baseball fan knows, pine tar doesn’t have to be very hot to be sticky. Shipyards did warm that tar to make it flow more easily, but pine tar starts to melt at about 140°F (60°C). That’s well above the ideal for bathwater, but far from the temperature of hot asphalt.Pine tar could be hot enough to injure someone. The Loyalist judge Peter Oliver complained that when a mob attacked Dr. Abner Beebe of Connecticut, “hot Pitch was poured upon him, which blistered his Skin.”[i] But other victims of tarring and feathering didn’t mention severe or lasting burns among their injuries. Rioters probably applied the tar with a mop or brush, lowering its temperature. Sometimes they tarred people more gently over their clothing.

Tarring and feathering undoubtedly caused pain and a lot of discomfort and inconvenience. But above all it was supposed to be embarrassing for the victim. Mobs performed the act in public as a humiliation and a warning—to the victim and anyone else—not to arouse the community again. There are no examples of people in Revolutionary America dying from being tarred and feathered.

2. Myth:

Rebellious Bostonians invented the tars-and-feathers treatment.Busted:

Some incidents of tar and feathers in pre-Revolutionary Boston became notorious emblems of American violence. That assault on John Malcolm inspired the British artist Philip Dawe to create a print titled “The Bostonian’s Paying the Excise-Man, or Tarring & Feathering.”[v]But the first example of such an assault in pre-Revolutionary America took place in the port of Norfolk, Virginia, in March 1766. A sea captain named William Smith wrote that seven men, including the mayor, had “bedawbed my body and face all over with tar and afterwards threw feathers upon me.” Those merchants and mariners also threw rotten eggs and stones at the captain, carted him “through every street in the town” with “two drums beating,” and finally tossed him off a wharf. The rioters had accused Smith of informing a royal official about a smuggler, though he denied that.[vi]

As the historian Ben Irvin found in a thorough survey of Revolutionary tarring and feathering,[vii] the next documented examples occurred in Salem and Newburyport, Massachusetts, in the summer of 1768. That’s why Peter Oliver, who had little good to say about Bostonians, wrote sarcastically, “The Town of Salem, about twenty miles from Boston, hath the Honor of this Invention.”[viii] In the fall of 1769 the practice popped up in New Haven, New York, and Philadelphia. Newspapers reporting these incidents described the process of tarring and feathering in detail, indicating that readers were not yet familiar with it.

When the punishment came to Boston, it appears that the first instigators were mariners from out of town. On 28 October 1769 a mob grabbed the sailor George Gailer, who had recently worked on the Customs patrol ship Liberty (confiscated the year before from John Hancock). According to the sailor, that crowd stripped him naked, tarred and feathered his skin, and paraded him around Boston in a cart for three hours, striking him with clubs, stones, and “a hand saw.” Gailer recognized some of his assailants and sued. The first three defendants were from Newport, Rhode Island, followed by three local men and a minor.[ix] In May 1770 another crowd in Boston tarred and feathered the Customs tide-waiter Owen Richards for seizing a ship from New London, Connecticut.[x]

A clear pattern emerges in reports of those early attacks: waterfront crowds tarred and feathered men who had busted smuggling operations. The punishment appears to have been a traditional form of maritime mobbing. There are scattered examples earlier in English law and history going back centuries. Once the Townshend duties of 1767 made smuggling and anti-smuggling the focus of the dispute between colonists and the London government, that gave tar and feathers political meaning.

Starting in January 1774, Boston’s Whig newspapers began to run advertisements signed “Joyce, Jun’r, Chairman of the Committee for Tarring and Feathering.” The historian Al Young interpreted those public notices as a way for the town’s political leadership to rein in spontaneous mobs and keep demonstrations under their control. “Joyce, Jun’r” actually repudiated the attack on John Malcolm, stating, “We reserve that Method for bringing Villains of greater Consequence to a Sense of Guilt and Infamy.”[xi] Indeed, the only tar-and-feathers assault in Boston after that date was carried out by the British 47th Regiment on a farmer they suspected had tried to lure soldiers into selling their guns.

3. Myth:

Pre-war mobs attacked high-class royal officials with tar and feathers.Busted:

In 1767 the London government appointed five Commissioners of the Customs for North America and put their headquarters in Boston. From the start those men were the focus of mariners’ resentment and criticism. At different times mobs surrounded their houses or chased them across the countryside. But none of those men were ever tarred and feathered. Nor were their high-level deputies, such as the collectors and inspectors. Nor were other royal appointees like governors, judges, sheriffs, or justices of the peace.Instead, pre-Revolutionary crowds reserved tar and feathers mainly for working-class Customs employees and other common men: tide-waiters and land-waiters, sailors on Customs ships, informers, and laborers who supported the Crown. British colonists lived in a deferential society in which everyone expected gentlemen to receive gentler treatment than the mass of ordinary men. Sometimes people would stick tar and feathers on a wealthy merchant’s shop or, as in rural Marlborough, Massachusetts, in June 1770, on a gentleman’s horse, but they did not attack those men themselves.

The closest a Boston mob came to tarring and feathering a gentleman occurred on 19 June 1770 when people seized Patrick McMaster, a Scottish-born merchant who was defying the town’s “non-importation” boycott on goods from Britain. Men placed him in a cart beside a barrel of tar. But with McMaster “fainting away from apprehension of what was to befall him,” a royal official wrote, the crowd “spared him this ignimony [sic], and contented themselves with leading him thro’ the town in the Cart to Roxbury, where they turned him out, spiting upon him.”[xii] The crowd showed less mercy to working-class men like George Gailer and Owen Richards.

In fact, it appears that tarring and feathering someone was a way to communicate that he wasn’t a gentleman, just as clubbing or horsewhipping a man was a way to signal that he wasn’t genteel enough to challenge to a duel. We see this in the exchange that led up to the attack on John Malcolm in January 1774. The little shoemaker George Robert Twelves Hewes criticized the Customs man for threatening a boy. Malcolm called Hewes “a vagabond,” and said “he should not speak to a gentleman in the street.” Soon Hewes replied, “be that as it will, I was never tarred nor feathered any how”—reminding Malcolm of an earlier incident in New Hampshire and hinting that he wasn’t a real gentleman at all. And then Malcolm clubbed Hewes on the head.[xiii]

As the Revolutionary War drew closer, class deference crumbled a little. In September 1774 a crowd in East Haddam, Connecticut, tarred and otherwise abused the physician and mill owner Abner Beebe.[xiv] Soon after the war began, in the summer of 1775, there was an explosion of tarring and feathering across many colonies, from Savannah to Litchfield. Among the targets was James Smith, a judge in Dutchess County, New York, who had tried to prevent a local committee from disarming “Tories.”[xv] Still, such attacks on upper-class men remained exceptions to the general pattern.

4. Myth:

Towns displayed tar barrels and bags of feathers on Liberty Poles.Busted:

Liberty Poles were flagpoles displaying the British Union flag. In 1769 a contingent of soldiers stationed in New York pulled down such a flagpole outside a tavern popular with local Whigs, evidently angered by their claim to superior patriotism. The locals erected a taller pole. When soldiers toppled that, too, the New Yorkers put up an even stronger one and called it a “Liberty Pole.” That tussle, reported in the newspapers, made Liberty Poles into a symbol of patriotic stubbornness. (The two sides also brawled, of course.) As America’s political conflict heated up in the early 1770s, towns vied to erect the tallest Liberty Pole around. But those poles displayed flags, not tar and feathers.[xvi]A tar barrel did appear beside a pole in Williamsburg, Virginia, in November 1774. A Loyalist merchant named James Parker told a friend, “At Wmsbg there was a Pole erected by Order of Col. Archd. Cary, a strong Patriot, opposite the Raleigh tavern upon which was hung a large mop & a bag of feathers, under it a bbl [barrel] of tar.”[xvii] Neither Parker nor another witness called that pole a “Liberty Pole,” and neither reported a flag as part of this threatening display.

Inspired by that report, in early 1775 Philip Dawe the printmaker published a political cartoon titled “The Alternative of Williams-Burg.” In the background of that picture stands a pole in the unmistakable shape of a gallows. Instead of leaving the heavy tar barrel on the ground, as Parker’s description suggested, the cartoon showed it hanging on the gallows alongside the bag of feathers. Colonial Williamsburg has modeled its depiction of a Liberty Pole bearing a barrel and feathers on this cartoon even though the London artist didn’t draw that scene from life and shaped his imagery to make a political point.[xviii]

5. Myth:

Tarring and feathering ended with the Revolution.Busted:

American culture came to associate tar and feathers with the Revolutionary period, but that simply lent the violent punishment a patriotic cachet when crowds revived it during other conflicts. And they did.In ante-bellum America, mobs tarred and feathered several people who spoke against slavery and threatened prominent abolitionists with the same treatment.[xix] Other crowds used tar and feathers on leaders of religious minorities: the Mormon leader Joseph Smith in 1832 and the Catholic priest John Bapst in 1851.

When the U.S. entered the First World War, crowds attacked some citizens who refused to cooperate with the war effort. Those riots spilled over into assaults on labor organizers, especially the anti-war Industrial Workers of the World, and on civil-rights activists.[xx] One victim, John Meints of Luverne, Minnesota, documented his injuries with photographs.[xxi]

More recent examples of tarring and feathering are rare and no longer seem to involve stripping off the victim’s clothing. In 1971 a branch of the K.K.K. tarred a Michigan school principal for advocating a celebration of the late Rev. Martin Luther King.[xxii] In Northern Ireland in 2007, two men thought to be in the I.R.A. carried out the ritual assault on a man they accused of dealing drugs.[xxiii] Tarring and feathering remains a powerful way to intimidate and humiliate perceived enemies outside the law.

[i] Peter Oliver’s Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion: A Tory View, Douglass Adair and John A. Schutz, editors (San Marino, Cal.: Huntington Library, 1961), 157.

[ii] Henry Hulton, “Some Account of the Proceedings of the People in New England; from the Establishment of a Board of Customs in America, to the breaking out of the Rebellion in 1775,” André deCoppet Manuscript Collection, Firestone Library, Princeton University, 224.

[iii] Ann Hulton, Letters of a Loyalist Lady (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1927), 71.

[iv] Frank W. C. Hersey, “Tar and Feathers: The Adventures of Captain John Malcolm,” Colonial Society of Massachusetts Publications, 34 (1941), 429-73. Walter Kendall Watkins, “Tarring and Feathering in Boston in 1770,” Old-Time New England, 20 (1929), 30-43. Audit Office Files, AO 13/75, 42, National Archives, United Kingdom.

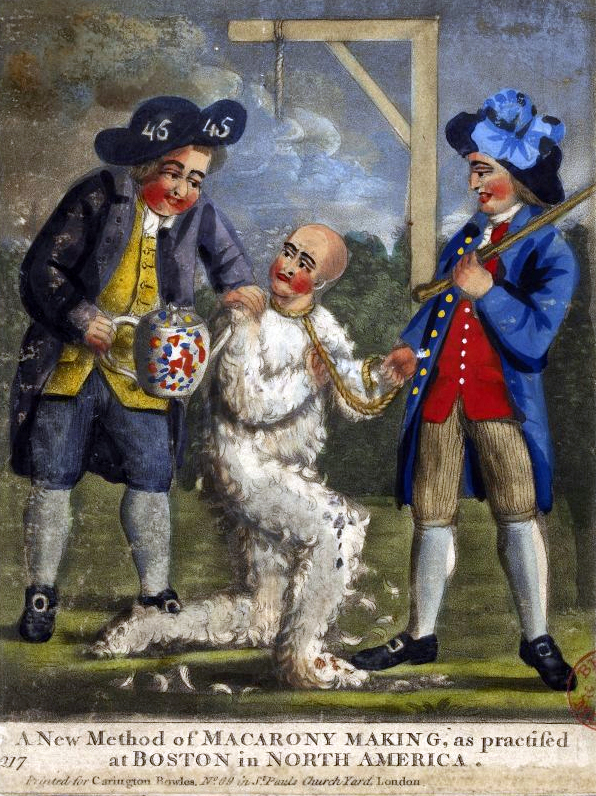

[v] Dawe also drew on John Malcolm’s experience for “A New Method of Macarony Making, as practised at Boston.” R. T. H. Halsey, n Dawes (New York: Grolier Club, 1904).

[vi] William Smith to Jeremiah Morgan, 3 Apr 1766, in “Letters of Governor Francis Fauquier,” William and Mary Quarterly, 1st series, 21 (1913), 167-8.

[vii] Benjamin H. Irvin, “Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768-1776,” New England Quarterly, 76 (2003), 197-238.

[ix] Legal Papers of John Adams, L. Kinvin Roth and Hiller B. Zobel, editors (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1965), 1:41-2.

[x] Audit Office Files, AO 13/75, 350. Treasury Files, T1 476/58, 60-2, 64-5, National Archives, United Kingdom.

[xi] Albert Matthews, “Joyce Junior,” Colonial Society of Massachusetts Publications, 8 (1902-04), 89-104. Alfred F. Young, “Tar and Feathers and the Ghost of Oliver Cromwell: English Plebeian Culture and American Radicalism,” in Liberty Tree: Ordinary People and the American Revolution (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 144-79. Philadelphia was the first American city to putatively have a Committee for Tarring and Feathering, which in November 1773 warned river pilots not to steer in a ship carrying tea; “To the Delaware Pilots” broadside, 27 Nov 1773, Library of Congress.

[xii] Hulton, “Some Account,” 166-7. Colin Nicolson, “A Plan ‘to banish all the Scotchmen’: Victimization and Political Mobilization in Pre-Revolutionary Boston,” Massachusetts Historical Review, 9 (2007), 55-102.

[xiii] Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 48.

[xiv] Joseph Spencer to Gov. Jonathan Trumbull, 14 Sept 1774, in Peter Force, editor, American Archives, 4th series, 1:787.

[xvi] Young, Liberty Tree, 346-54, 384. David Hackett Fischer, Liberty and Freedom: A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 37-49.

[xvii] A. Francis Steuart, “Letters from Virginia, 1774-1781,” Magazine of History with Notes and Queries, 3 (1906), 156.

[xviii] Robert Doares, “The Alternative of Williams-Burg,” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Spring 2006, 20-5.

[xix] <http://www.sethkaller.com/item/551-Threatening-to-Tar-and-Feather-an-Abolitionist-in-Boston>.

No comments:

Post a Comment